Introduction

When we were looking for a configuration management engine to integrate with SUSE Manager, we discussed Ansible with some colleagues that were familiar with it.

At the end, we ended choosing Salt for SUSE Manager 3, but I still often get the question “Why not Ansible?”.

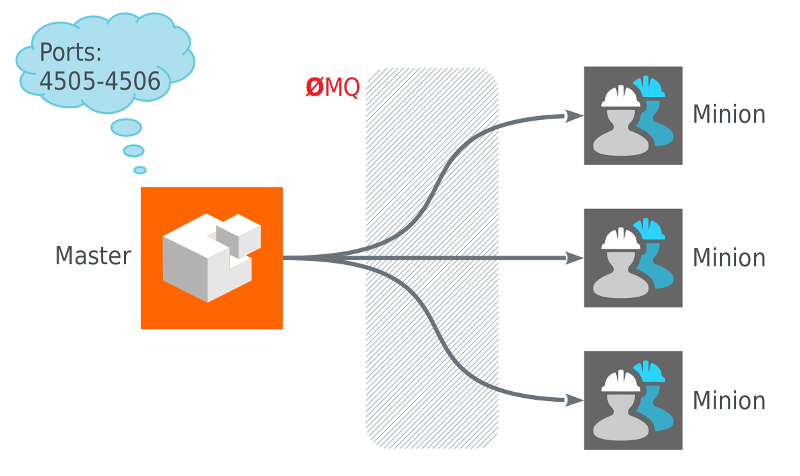

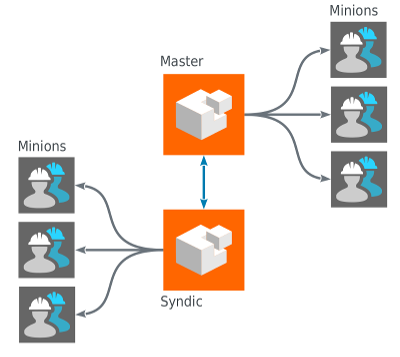

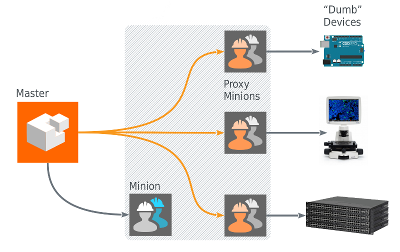

The first part of the answer had to do that the master-minion architecture of Salt results in a bunch of interesting features and synergies with the way SUSE Manager operates: real-time management, event-bus, etc. Salt is much more of a framework than a simple “command line tool”. The minion/master pair is one of the tools built over that framework, but not the only one.

For example, you can create more scalable topoligies using the concept of syndics:

Or manage dumb devices with the concept of Salt proxies:

It is worth to learn the whole framework.

However, for a small DevOp team collaborating via git, the model of running Ansible from their workstations to a bunch of nodes defined in a text file is very attractive, and gives you a nice way to learn and experiment with it.

The second part of the answer is: Salt allows you to do this too. It is called salt-ssh. So lets take this Ansible tutorial and show how you would do the same with salt-ssh.

Install

This means there’s usually a “central” server running Ansible commands, although there’s nothing particularly special about what server Ansible is installed on. Ansible is “agentless” - there’s no central agent(s) running. We can even run Ansible from any server; I often run Tasks from my laptop.

The salt package is made of various components, among others:

salt: the framework, libraries, modules, etc.salt-minion: the minion daemon, runs on the managed hosts.salt-master: the master daemon, runs on the management server.salt-ssh: a tool to manage servers over ssh.

If you want to run Salt like Ansible, you only need to install salt-ssh in your machine (the machine where you want to run tasks from).

You don’t need anything else than Python on the hosts you will manage.

Well, there are a couple of other packages required

ssh $HOST zypper -n install python-pyOpenSSL python-xml

Salt is available out of the box on openSUSE Leap and Tumbleweed so if you are using them just type:

zypper in salt-ssh

For other platforms, please refer to the install section of the Salt documentation.

Self contained setup

It is common to put all the project in a single folder. In Ansible you can put the hosts file in a folder, and the playbooks in a subfolder. To accomplish this with salt-ssh.

- Create a folder for your project, eg:

~/Project. - Create a file named

Saltfilein your~/Project.

salt-ssh:

config_dir: etc/salt

max_procs: 30

wipe_ssh: True

Here we tell Salt that the configuration directory is now relative to the folder. You can name it as you want, but I prefer myself to stick to the same conventions, so /etc/salt becomes ~/Project/etc/salt.

Then create ~/Project/etc/salt/master:

root_dir: .

file_roots:

base:

- srv/salt

pillar_roots:

base:

- srv/pillar

And create both trees:

mkdir -p srv/salt mkdir -p srv/pillar

Salt will also create a var directory for the cache inside the project tree, unless you chose a different path. What I do is to put var inside .gitignore.

Managing servers

Ansible has a default inventory file used to define which servers it will be managing. After installation, there’s an example one you can reference at /etc/ansible/hosts.

The equivalent file in salt-ssh is /etc/salt/roster.

That’s good enough for now. If needed, we can define ranges of hosts, multiple groups, reusable variables, and use other fancy setups, including creating a dynamic inventory.

Salt can also provide the roster with custom modules. Funnily enough, ansible is one of them.

As I am using a self-contained setup, I create ~/Project/etc/salt/roster:

node1: host: node1.example.com node2: host: node2.example.com

Basic: Running Commands

Ansible will assume you have SSH access available to your servers, usually based on SSH-Key. Because Ansible uses SSH, the server it’s on needs to be able to SSH into the inventory servers. It will attempt to connect as the current user it is being run as. If I’m running Ansible as user vagrant, it will attempt to connect as user vagrant on the other servers.

salt-ssh is not very different here. Either you already have access to the server, otherwise it will optionally ask you for the password and deploy the generated key-pair etc/salt/pki/master/ssh/salt-ssh.rsa.pub to the host so that you have access to it in the future.

So, in the Ansible tutorial, you did:

$ ansible all -m ping

127.0.0.1 | success >> {

"changed": false,

"ping": "pong"

}

The equivalent in salt-ssh would be:

salt-ssh '*' test.ping

node1:

True

node2:

True

Just like the Ansible tutorial covers, salt-ssh also has options to change the user, output, roster, etc. Refer to man salt-ssh for details.

Modules

Ansible uses “modules” to accomplish most of its Tasks. Modules can do things like install software, copy files, use templates and much more.

If we didn’t have modules, we’d be left running arbitrary shell commands like this:

ansible all -s -m shell -a 'apt-get install nginx'

However this isn’t particularly powerful. While it’s handy to be able to run these commands on all of our servers at once, we still only accomplish what any bash script might do.

If we used a more appropriate module instead, we can run commands with an assurance of the result. Ansible modules ensure indempotence - we can run the same Tasks over and over without affecting the final result.

For installing software on Debian/Ubuntu servers, the “apt” module will run the same command, but ensure idempotence.

ansible all -s -m apt -a 'pkg=nginx state=installed update_cache=true'

127.0.0.1 | success >> {

"changed": false

}

The equivalent in Salt is also called “modules”. There are two types of modules: Execution modules and State modules. Execution modules are imperative actions (think of install!). State modules are used to build idempotent declarative state (think of installed).

There are two execution modules worth to mention:

- The

cmdmodule, which you can use to run shell commands when you want to accomplish something that is not provided by a built-in execution module. Taking the example above:

salt-ssh '*' cmd.run 'apt-get install nginx'

- The

statemodule, which is the execution module that allows to apply state modules and more complex composition of states, known asslsfiles.

salt-ssh '*' pkg.install nginx

You don’t need to use the apt module, as it implements the virtual pkg module. So you can use the same module on every platform.

On Salt you would normally use the non-idempotent execution modules from the command line and use the idempotent state module in sls files (equivalent to Ansible’s playbooks).

If you still want to apply state data like ansible does it:

salt-ssh '*' state.high '{"nginx": {"pkg": ["installed"]}}'

Basic Playbook

Playbooks can run multiple Tasks and provide some more advanced functionality that we would miss out on using ad-hoc commands. Let’s move the above Task into a playbook.

The equivalent in Salt is found in states.

Create srv/salt/nginx/init.sls:

nginx: pkg.installed

To apply this state, you can create a top.sls and place it in srv/salt:

base:

`*`:

- nginx

This means, all hosts should get that state. You can do very advanced targetting of minions. When you write a top, you are defining what it will be the highstate of a host.

So when you run:

salt-ssh '*' state.apply

You are applying the highstate on all hosts, but the highstate of each host is different for each one of them. With the salt-ssh command you are defining which hosts are getting their configuration applied. Which configuration is applied is defined by the top.sls file.

You can as well apply a specific state, even if that state does not form part of the host highstate:

salt-ssh '*' state.apply nginx

Or as we showed above, you can use state.high to apply arbitrary state data.

Handlers

Salt has a similar concept called events and reactors which allow you to define a fully reactive infrastructure.

For the example given here, a simple state watch argument will suffice:

nginx:

pkg.installed: []

service.running:

- watch: pkg: nginx

Note:

The full syntax is:

someid:

pkg.installed:

name: foo

But if name is missing, someid is used, so you can write:

#+BEGIN_SRC yaml foo: pkg.installed #+END_END

More Tasks

Looking at the given Ansible example:

{% raw %}

---

- hosts: local

vars:

- docroot: /var/www/serversforhackers.com/public

tasks:

- name: Add Nginx Repository

apt_repository: repo='ppa:nginx/stable' state=present

register: ppastable

- name: Install Nginx

apt: pkg=nginx state=installed update_cache=true

when: ppastable|success

register: nginxinstalled

notify:

- Start Nginx

- name: Create Web Root

when: nginxinstalled|success

file: dest={{ docroot }} mode=775 state=directory owner=www-data group=www-data

notify:

- Reload Nginx

handlers:

- name: Start Nginx

service: name=nginx state=started

- name: Reload Nginx

service: name=nginx state=reloaded

{% endraw %}

You can see that Ansible has a way to specify variables. Salt has the concept of pillar which allows you to define data and then make that data visible to hosts using a top.sls matching just like with the states. Pillar data is data defined on the “server” (there is a equivalent grains for data defined in the client).

Edit srv/pillar/paths.sls:

{% raw %}

docroot: /var/www/serversforhackers.com/public

{% endraw %}

Edit srv/pillar/top.sls and define who will see this pillar (in this case, all hosts):

base:

'*':

- paths

Then you can see which data every host sees:

salt-ssh '*' pillar.items

node1:

----------

docroot:

/var/www/serversforhackers.com/public

node2:

----------

docroot:

/var/www/serversforhackers.com/public

With this you can make sensitive information visible on the hosts that need it. Now that the data is available, you can use it in your sls files, you can add to

{% raw %}

nginx package:

pkg.installed

nginx service:

service.running:

- watch: pkg: 'nginx package'

nginx directory:

file.directory:

- name: {{ pillar['docroot'] }}

{% endraw %}

Which can be abbreviated as:

{% raw %}

nginx:

pkg.installed: []

service.running:

- watch: pkg: nginx

{{ pillar['docroot'] }}:

file.directory

{% endraw %}

Roles

Roles are good for organizing multiple, related Tasks and encapsulating data needed to accomplish those Tasks. For example, installing Nginx may involve adding a package repository, installing the package and setting up configuration. We’ve seen installation in action in a Playbook, but once we start configuring our installations, the Playbooks tend to get a little more busy.

There is no 1:1 concept in Salt as it already organizes the data around a different set of ideas (eg: gains, pillars), but for the utility of the specific Ansible tutorial, lets look at a few examples.

Files

Every thing you add to the file_roots path (defined in etc/salt/master) can be accessed using the Salt file server. Lets say we need a template configuration file, you can put it in ’srv/salt/nginx/myconfig` (you can use jinja2 templating on it), and then refer to it from the state:

/etc/nginx/myconfig:

file.managed:

- source: salt://nginx/myconfig

Template

You can use Jinja2 templating in states and files, and you can refer to grain and pillar data from them. Salt already include a long list of built-in grains you can use (see grains.items) and you can also create your own grain modules to gather other data.

A common use of pillar data is to distribute passwords to the configuration files. While you can define pillar data in the srv tree, because you can also define external pillars you can source your data from anywhere.

Running the role

As mentioned before, you can apply the state by either making it part of the host highstate or apply it explicitly.

Let’s create a “master” yaml file which defines the Roles to use and what hosts to run them on: File server.yml:

---

- hosts: all

roles:

- nginx

This is equivalent to the top.sls file in srv/salt (with a less powerful matching system).

base:

`*`:

- nginx

Then we can run the Role(s):

salt-ssh '*' state.apply

Would apply what top.sls defines.

Facts

These are equivalent to grains, and you can see what grains you have available by calling:

salt-ssh '*' grains.items

You can use them from Jinja2 as grains:

{% raw %}

{% if grains['os_family'] == 'RedHat' %}

...

{% endif %}

{% endraw %}

If you need a custom grain definition, you can write your own and distribute them from the server.

Vault

The equivalent in Salt would be to use the Pillar. If you need encryption support you have various options:

- Use a external pillar which fetches the data from a vault service

- Use the renderer system and add the gpg renderer to the chain. (Disclaimer: I haven’t tried this myself).

Example: Users

You will need a pillar:

admin_password: $6$lpQ1DqjZQ25gq9YW$mHZAmGhFpPVVv0JCYUFaDovu8u5EqvQi.Ih deploy_password: $6$edOqVumZrYW9$d5zj1Ok/G80DrnckixhkQDpXl0fACDfNx2EHnC common_public_key: ssh-rsa ALongSSHPublicKeyHere

And then refer to it from the user state:

{% raw %}

admin:

user.present:

- password: {{ pillar['admin_password'] }}

- shell: /bin/bash

sshkeys:

ssh_auth.present:

- user: admin

- name: {{ pillar['common_public_key'] }}

{% endraw %}

In order to refresh the pillar data, you can use:

salt-ssh '*' saltutil.refresh_pillar

Recap

So, this is how you use Salt in a way similar to Ansible. The best part of this is that you can start learning about Salt without having to deploy a Salt master/minion infrastructure.

The master/minion infrastructure brings a whole new set of possibilities. The reason we chose Salt is because here is where it starts, and not where it ends.

Thanks & Acknowledgements

- Chris Fidao for the original Ansible tutorial.

- Konstantin Baikov for corrections and suggestions.