RPM Packaging Tutorial

Document revisions

| Date | Changes |

|---|---|

| 09.10.2018 | Fixed typos |

| 20.02.2018 | Merged contributions |

| 13.03.2017 | Added links about kmp drivers |

| 08.03.2017 | First release |

What is a package

A package is a way of distributing software on Linux systems. A single application is distributed as one or more packages, usually the main package containing the program, and then some optional or secondary packages.

On some platforms, applications are self-contained into a directory. This makes installing an app just adding a folder, and uninstalling the app, removing it.

Linux systems tend to share as much as components as possible. This is due partly to some advantages of this philosophy, but it is due mostly because in the Linux ecosystem, the whole universe is built by the same entity, except for a few 3rd party applications. This makes easy to assume that a library is available for all applications to consume. In a MacOS system, only the core comes from a single vendor, and all applications come from 3rd parties. It is therefore harder to make assumptions, and they tend to ship their own version of any depending component, with the exception of everything documented as the “platform”.

For example, if an application requires the SSL library and the Qt toolkit. On a Linux system, it will likely use both components from the Linux distribution, while the MacOS version will likely use the SSL library from the OS, but ship its own version of Qt, as it is not a standard MacOS library.

Anatomy of a package

Lets start with a famous UNIX tool: rsync.

So a package is an archive file:

rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm

containing all files related to the application:

$ rpm -qpl rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm /etc/logrotate.d/rsync /etc/rsyncd.conf /etc/rsyncd.secrets /etc/sysconfig/SuSEfirewall2.d/services/rsync-server /etc/xinetd.d/rsync /usr/bin/rsync /usr/bin/rsyncstats /usr/lib/systemd/system/rsyncd.service /usr/sbin/rcrsyncd /usr/sbin/rsyncd /usr/share/doc/packages/rsync /usr/share/doc/packages/rsync/COPYING /usr/share/doc/packages/rsync/NEWS /usr/share/doc/packages/rsync/README /usr/share/doc/packages/rsync/tech_report.tex /usr/share/man/man1/rsync.1.gz /usr/share/man/man5/rsyncd.conf.5.gz

plus some extra metadata. This metadata includes but it is not limited to:

Name,Summary,Description,License, etc.

$ rpm -qpi rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm Name : rsync Version : 3.1.2 Release : 1.5 Architecture: x86_64 Install Date: Wed 26 Oct 2016 01:31:12 PM CEST Group : Productivity/Networking/Other Size : 636561 License : GPL-3.0+ Signature : RSA/SHA256, Mon 17 Oct 2016 02:32:40 AM CEST, Key ID b88b2fd43dbdc284 Source RPM : rsync-3.1.2-1.5.src.rpm Build Date : Mon 17 Oct 2016 02:32:26 AM CEST Build Host : lamb18 Relocations : (not relocatable) Packager : http://bugs.opensuse.org Vendor : openSUSE URL : http://rsync.samba.org/ Summary : Versatile tool for fast incremental file transfer Description : Rsync is a fast and extraordinarily versatile file copying tool. It can copy locally, to/from another host over any remote shell, or to/from a remote rsync daemon. It offers a large number of options that control every aspect of its behavior and permit very flexible specification of the set of files to be copied. It is famous for its delta-transfer algorithm, which reduces the amount of data sent over the network by sending only the differences between the source files and the existing files in the destination. Rsync is widely used for backups and mirroring and as an improved copy command for everyday use. Distribution: openSUSE Tumbleweed

- What does the package requires to be also installed in order to work

(

Requires)

$ rpm -qp --requires rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm /bin/sh /usr/bin/perl config(rsync) = 3.1.2-1.5 coreutils diffutils fillup grep libacl.so.1()(64bit) libacl.so.1(ACL_1.0)(64bit) libc.so.6()(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.10)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.14)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.15)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.2.5)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.3)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.3.4)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.4)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.6)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.7)(64bit) libc.so.6(GLIBC_2.8)(64bit) libpopt.so.0()(64bit) libpopt.so.0(LIBPOPT_0)(64bit) libslp.so.1()(64bit) rpmlib(CompressedFileNames) <= 3.0.4-1 rpmlib(PayloadFilesHavePrefix) <= 4.0-1 rpmlib(PayloadIsLzma) <= 4.4.6-1 sed systemd

For example, a package may need a library, or an executable that is called during runtime.

- What does the package provide for other packages to work (

Provides)

$ rpm -qp --provides rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm config(rsync) = 3.1.2-1.5 rsync = 3.1.2-1.5 rsync(x86-64) = 3.1.2-1.5

Installing packages

When a package is installed, the content (list of files) is placed on

the system at the location of each file path relative to the root (/)

folder.

Additionally, the metadata of the package and the fact that is installed

is recorded in a system-wide database located in /var/lib/rpm, managed

by the rpm tool, which is the tool that manages packages at the lowest

level.

Packages can be installed with the rpm tools:

$ rpm -U rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm

Once you do this, you can perform the same queries without specifying

the -p option and use what is called the NVRA

(name-version-release-architecture, rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64) or a

subset of it, e.g. just name (rsync).

$ rpm -q --provides rsync

The rpm tool will not help you if the dependencies of the package are

not met at installation time. It will just refuse to install the package

to avoid having the system in an inconsistent state.

Features like an automatical finding of the required packages and

retrieving them are implemented in higher-level tools like zypper.

Dependency matching

You saw above that a package has a list of Requires and Provides.

Those aren’t package names, but arbitrary symbols. A package can require

any string of text and provide anything.

The main rule is that each package provides its own name. So the rsync

package Provides: rsync.

You saw that rsync requires /bin/sh. While this looks like a file

name, here it is an arbitrary symbol and the meaning is given by the

whole distribution. Why it does not require a package named sh

instead? Well, this is for various reasons:

- It provides a layer of indirection that makes the system cohesive.

/bin/sh is a capability provided by the bash package. This allows

rsync to depend on any shell implementation as long as it provides that

symbol.

The distribution build system will scan all executables a package

installs in a system and inject automatically those Provides, so that

the packager does not need to take care of them.

We will see later that the same is done with libraries. Instead of

rsync depending on the glibc package, when glibc was built, the

build system scanned the content, found /lib64/libc.so.6 and injected

a Provides: libc.so.6()(64bit) into the glibc metadata. In the case

of shared libraries it is not that important where they are located, as

the linker configuration takes care of that. When the rsync package

was built (glibc had to be installed at that point to build it), the

build system scanned the executable /usr/lib/rsync and realized it was

linked against libc.so.6:

$ ldd /usr/bin/rsync

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffccb34a000)

libacl.so.1 => /lib64/libacl.so.1 (0x00007fc406028000)

libpopt.so.0 => /usr/lib64/libpopt.so.0 (0x00007fc405e1b000)

libslp.so.1 => /usr/lib64/libslp.so.1 (0x00007fc405c02000)

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x00007fc405863000)

libattr.so.1 => /lib64/libattr.so.1 (0x00007fc40565e000)

libcrypto.so.1.0.0 => /lib64/libcrypto.so.1.0.0 (0x00007fc4051c4000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib64/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007fc404fa7000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00005653cd048000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib64/libdl.so.2 (0x00007fc404da3000)

libz.so.1 => /lib64/libz.so.1 (0x00007fc404b8d000)

Therefore, it injected Requires: libc.so.6()(64bit) to the rsync

package.

Compare it to other packaging systems. Package musicplayer requires

libsound. /usr/bin/musicplayer links to /usr/lib64/libsound.so.5.

Later, musicplayer is rebuilt against a newer libsound, which is not

published. The user installs musicplayer with no issues because it

only Requires: libsound (as in package name). Then when he/she tries

to run it:

$ musicplayer error while loading shared libraries: libsound.so.7: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

The layer of indirection of automatically injected dependencies prevents this manual work of keeping dependencies in sync. Package provide what they really carry (because provides are injected by advanced scanners), and packages require what they really need (because requires are injected by scanning executables, scripts for shebangs, etc.

This makes rpm based distributions using these conventions highly

cohesive. It makes less problematic to do upgrades without breaking your

system. At the same time, the conventions and indirections between

provides and requires, allow for packages to depend on more abstract

capabilities, instead of specific package names (which sometimes get

renamed, split, obsoleted, etc). Yes, you can be sure the vim package

provides vi.

There are also other dependencies with more advances purposes:

Conflicts, Obsoletes, etc. You may already guess what purposes they

have.

Weak dependencies

Not everything is as strict. Sometimes a package works better if another package is present. Sometimes a package enhances the functionality of another package, however in neither case they are required. For this purpose, packages can have:

Recommends: a soft version of requires. If the recommended packages are not installed, the package will be installed anyway. Higher level tools, however, may pull automatically recommended packages based on user settings. The reverse of this dependency isSupplements. For example aspellcheckercouldSupplementsanoffice-suitepackage.SuggestsandEnhancesare the forward and backward version ofRecommendsandSupplementsin a weaker version.

Working with packages

For daily system administration and maintenance, the rpm tool is not

sufficient. You will quickly fall into what is called the “dependency

hell”. Downloading packages by hand in order to satisfy a dependency to

quickly realize this new package also requires something else.

This problem is solved by a tool that implements a solver. The solver takes:

- The list of installed packages (and therefore all its dependencies)

- The list of available packages

- The user request (“install package foo”, “upgrade system”)

The solver performs an operation that is finding the best solution to a problem that has many solutions. Therefore “best” is defined by policies, user settings, the distribution itself, etc.

On SUSE systems, the solver is implemented by the

libsolv project. This engine

implements both a satisfiability algorithm and an efficient way to

represent the problem in memory. It was developed originally by Michael

Schroeder at SUSE, but nowadays it powers even other distribution

package managers, like Fedora’s

dnf.

The rest of the package manager includes:

- Handling of package repositories

- Checking the integrity of packages

- Fetching remote packages

- Reading and honoring user/system policies

This functionality in SUSE systems is implemented by the

ZYpp library, which also

includes a command-line tool called zypper. While tools like

YaST also interact with ZYpp, on the

console you will likely interact with zypper.

$ zypper install rsync-3.1.2-1.5.x86_64.rpm

Will, unlike rpm, figure out what else your system is missing, retrieve it, and then install all the required packages in the right order. It will also warn you if another package conflicts with what you are installing, of if the operation has more than one solution, and ask you for decisions on what to do.

Now, when we say “retrieve other packages”, the question arises. From where?

Repositories

You can see that zypper can install a package directly from an rpm

file. Now, if there is the need for installing dependencies or

retrieving packages i.e. when you upgrade a system, you will need a

“library” of packages. This is what is called a repository. A repository

is:

- A collection of packages

- A set of metadata files

The metadata is nothing more than the information present in the rpm file (Name, Description, Dependencies). The metadata allows the package manager to operate with the repository without having all rpm files locally. Every operation is processed used what we know about the package, and then rpm files are retrieved on demand at installation time.

$ zypper lr # | Alias | Name | Enabled | GPG Check | Refresh --+----------------+----------------+---------+-----------+-------- 1 | non-oss | NON-OSS | Yes | ( p) Yes | Yes 2 | oss | OSS | Yes | ( p) Yes | Yes 3 | oss-update | OSS Update | Yes | ( p) Yes | Yes 4 | update-non-oss | Update Non-Oss | Yes | ( p) Yes | Yes

A system normally will have the following repositories:

- The base repository, which contains all the distribution packages.

- Additional modules, addons products or extensions.

- An update repository for each base product or extension

Running list repositories with -u i.e. zypper lr -u will show you

the URI of the repository. e.g.

http://download.opensuse.org/update/leap/42.2/oss/. If you visit this

URI, you will see:

- a

x86_64directory containing all architecture-dependent packages (i.e. ones that contain executables, shared libraries, etc) - a

noarchdirectory containing architecture-independent packages (i.e. ones containing data or scripts) - a

repodatadirectory, containing the metadata for all packages.

The metadata for this type of repositories consists in a

repodata/repomd.xml file index, that is signed (repomd.xml.asc)

using a key already present in the original system.

repodata/repomd.xml refers to other metadata file with their

checksums. The most important is primary.xml which contains all

package dependencies.

If you have a directory with rpm packages, you can create the metadata

for them using the createrepo tool. After that, you can serve that

repository via HTTP.

If you have a directory with rpms you want to use as a repository, you

don’t need to add metadata. ZYpp allows to have a plain local

directory as a repository, and will read the metadata directly from the

rpm files into its cache.

Refreshing a repository

$ zypper ref

While the base repository of the distribution is normally immutable, repositories like the one containing updates get new content often. The meaning of refreshing a repository is to get the up to date version of the metadata locally, so that all operations (solving, retrieval) match the current content of the repository.

If a repository is out of date, it means the local metadata represents a previous version of the repository content. We would solve, and likely fetch packages, but those packages may not exists in the repository anymore, so you will get an error at retrieval time.

The list of repositories of the system is kept in /etc/zypp/repos.d.

zypper provides most of repository operations in a safer way than

messing with those files by hand.

During refresh, metadata is cached locally at /var/cache/zypp/raw and

converted to an efficient format for solving operations in

/var/cache/zypp/solv.

Services

Services are a higher-level version of repositories. It is another index that lists repositories. When the system is subscribed to a service, refreshing the service will result in a new list of repositories, and the package manager will add new ones or remove obsolete ones.

Services are used for example on SUSE Linux Enterprise with the SUSE Customer Center. A customer is subscribed to a service provided by SCC using a credential. The customer, based on his entitlements, can “activate” a new product. SUSE Customer Center knows about those activations, and on service refresh, it will provide a new list of repositories that includes the new activated product.

Services can be remote (like SCC), or local (via a plugin installed on

the system). The package manager asks the plugin for a list of

repositories. It is up to the plugin to build that list. This is

normally used for integration with other systems. The connectivity

between zypper and

Spacewalk/SUSE

Manager was originally implemented using a local plugin.

Repository sources

If you are using SUSE Linux Enterprise, your repositories will appear

after the SUSEConnect tool registers your product against the

SUSE Customer Center.

If you are on openSUSE, the default installation will setup the base and update repositories. Additionally, there is a lot of content published by the community on the build service projects (but please note that packages from unofficial repositories are not reviewed by openSUSE) or via projects like packman.

SUSE Linux Enterprise users can take advantage of the community content via the Package Hub.

Other package manager operations

You can use zypper lu to list updates. zypper up to update them.

You can lock packages to avoid them being removed or pulled-in using

zypper addlock zypper removelock. You can also list active locks

with zypper locks.

The distribution upgrade operation dup is used to do destructive

upgrades. This means packages may be suggested for removal as

dependencies like Obsoletes are taken into account. It is usually used

for upgrading major releases or to update rolling distributions like

Tumbleweed. It has to be

used with care.

Other solvable types (Products, Patterns, System)

The package manager solver loads all available and installed packages to do the solving. However, there are other entities similar to packages that also have dependencies.

Patterns

Patterns are used to install a collection of software in a comfortable way. For example you can install a working Laptop-oriented system with:

$ zypper install -t pattern laptop

But where do patterns come from? They don’t exist on their own. The

package managers create them dynamically from packages names

patterns-XXXXXX which have a special set of dependencies. So

installing a pattern would actually install the package representing

that pattern. The other way around is true, if you install the package

representing the pattern, it will make the system look like the pattern

is installed.

$ zypper info --provides patterns-desktop-laptop would show you some

of the magic behind patterns (equivalent to

rpm -q --provides patterns-desktop-laptop).

Products

Similar to patterns, products can be queried with:

$ zypper search -t product

Product comes from a package called XXXXXX-release which has some

special dependencies (rpm -q --provides openSUSE-release). The release

package/product installs some information in /etc/products.d that is

used by other tools to get information about the base and addons

products installed.

Patches

Patches are used for updates and described by the updateinfo.xml

section of the metadata. They represent an entity that conflicts with

older versions of one or more packages. Installing a patch does not

install packages, but generates a conflict in the solver that ends with

the affected version of packages being upgraded.

Patches also carry additional property, like the CVE identifiers of the issues they fix or links to bug tracker incidents.

System

During solving, there is one entity providing dependencies that is used

to match locale and hardware information. If you have a WLAN card, the

package manager will dynamically read /sys/devices and make this

entity have provides like:

Provides :modalias(pci:v0000104Cd0000840[01]sv*sd*bc*sc*i*)

Then, a package providing a WLAN driver for some cards (e.g.

wlan-kmp-default), could have the following dependencies:

Supplements: modalias(kernel-default:pci:v0000104Cd0000840[01]sv*sd*bc*sc*i*) Supplements: modalias(kernel-default:pci:v0000104Cd00009066sv*sd*bc*sc*i*) Supplements: modalias(kernel-default:pci:v000010B7d00006000sv*sd*bc*sc*i*)

Which results in that at solving time, if the hardware is present, the driver will be selected automatically.

Something similar is done with translation packages and the current configured system locale.

Important notes

What is important to note is that all those types are only really

present at solving time. In reality, your system is only packages, and

all information comes from the installed packages. Every operation on

patches, patterns and products result in a package operation. This is to

make the package manager compatible with the lower level rpm tool.

Creating packages

Packages are created providing a so-called .spec file. A spec file

defines the attributes of the package, explicit dependencies (others are

injected as we already mentioned), and how the content of the package is

created. A very simple spec file would be:

Name: mypackage

Version: 1.0

Release: 0

License: MIT

Summary: Dummy package

BuildRoot: %{_tmppath}/%{name}-%{version}-build

%description

Dummy text

%install

mkdir -p %{buildroot}%{_datadir}/%{name}

touch %{buildroot}%{_datadir}/%{name}/CONTENT

%files

%defattr(-,root,root)

%{_datadir}/%{name}/CONTENT

%changelog

This spec file just creates a directory /usr/share/mypackage and puts

a dummy CONTENT file in it.

spec files are heavily defined by macros that make sure that paths and

values are specified by the distribution. Those macros are shipped by

the base distribution and are located in /usr/lib/rpm and /etc/rpm.

Other packages may contribute more macros. For example the macros

defined in /usr/lib/rpm/golang-macros.rb are provided by the

golang-packaging package and are useful to create packages that use

the Go language.

Common macros

When building spec files, you should be familiar with

macros

like %{_prefix}, %{_datadir}, %{_mandir}, %{_libdir},

%{_bindir}, etc. You can evaluate a macro like this:

$ rpm --eval "%{_libdir}"

/usr/lib64

Sub-packages

Sometimes from a single source you will build multiple components that are independent of each other.

The sources for an Office Suite may result in:

- A Word Processor

- A Spreadsheet

- Common libraries

- Development files

For this, you can declare

subpackages, which

is an independent description and attributes section for each component.

The build section is common, and then again in the %files section, you

will declare which files go to each subpackage. In this case you would

end with something like:

office-wordprocessoroffice-spreadsheetlibofficeoffice-devel

Building with rpmbuild

You can build a package with the rpmbuild tool. It requires the spec

file to be in a specific location, so I usually tweak the standard

configuration so that spec files are searched in the current directory:

$ cat ~/.rpmmacros

%topdir /space/packages

%_builddir %{topdir}/build

%_rpmdir %{topdir}/rpms

%_sourcedir %(echo $PWD)

%_specdir %(echo $PWD)

%_srcrpmdir %{topdir}/rpms

As you can see, I also configure it so that built packages are saved in

/space/packages. Tweak that to your own preferences.

Once I have this setup, I can do:

$ rpmbuild -bb mypackage.spec Executing(%install): /bin/sh -e /var/tmp/rpm-tmp.lVzwnj + umask 022 + cd /space/packages/build + mkdir -p /home/duncan/rpmbuild/BUILDROOT/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64/usr/share/mypackage + touch /home/duncan/rpmbuild/BUILDROOT/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64/usr/share/mypackage/CONTENT + /usr/lib/rpm/brp-compress + /usr/lib/rpm/brp-suse Processing files: mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64 Provides: mypackage = 1.0-0 mypackage(x86-64) = 1.0-0 Requires(rpmlib): rpmlib(CompressedFileNames) <= 3.0.4-1 rpmlib(PayloadFilesHavePrefix) <= 4.0-1 Checking for unpackaged file(s): /usr/lib/rpm/check-files /home/duncan/rpmbuild/BUILDROOT/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64 Wrote: /space/packages/rpms/x86_64/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64.rpm Executing(%clean): /bin/sh -e /var/tmp/rpm-tmp.0xLGri + umask 022 + cd /space/packages/build + /usr/bin/rm -rf /home/duncan/rpmbuild/BUILDROOT/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64 + rm -rf filelists

Now I can verify the content of the package:

% rpm -qpl /space/packages/rpms/x86_64/mypackage-1.0-0.x86_64.rpm /usr/share/mypackage/CONTENT

As you can see, everything that we put into the %{buildroot} ended as

content of the package.

Now the term “building a package” can have two meanings. One is assembling the package from existing content. You could build your application in Jenkins, take the built artifacts and use the spec file to package it.

However, where rpm really shines is that you can build the application in the spec file itself, and use the distribution and dependencies to setup the build environment.

A common use case to illustrate this is the typical Linux application

built with configure && make && make install. Lets try to build a

package for gqlplus, an alternative

client for Oracle databases.

Provided that you have readline and ncurses development headers, you can

build this application just unpacking the tarball and performing the

commands mentioned above. Some programs require an extra step with

autoconf in order to generate the configure script. This is specific

to building software and has nothing to do with packaging. Certainly

building a Qt based program will be a different experience, and if you

build a Java application, you will have to deal with other tools.

When you do ./configure you would need to pass the right --prefix.

This is where macros help you. You could do

configure --prefix=%{_prefix}, however, there is a better macro called

%configure which takes care and sets most of the configure options

(try expanding it: echo $(rpm --eval '%configure'))

Now, the package can’t build if some libraries are not present, a C

compiler is there, and the basic build tools (make) are not available.

That is what BuildRequires are for. They define what packages are

needed for building, but not necessarily at runtime.

On the other hand, the original oracle-instantclient-sqlplus package

is required at runtime, but we don’t need it to build our package.

Name: gqlplus

Version: 1.15

Release: 0

License: GPL-2.0

Summary: A drop-in replacement for sqlplus, an Oracle SQL client

Url: http://gqlplus.sourceforge.net/

Group: Productivity/Databases/Clients

Source0: %{name}-%{version}.tar.bz2

BuildRequires: readline-devel

BuildRequires: ncurses-devel

BuildRequires: gcc make autoconf automake

BuildRoot: %{_tmppath}/%{name}-%{version}-build

Requires: oracle-instantclient-sqlplus

%description

GQLPlus is a drop-in replacement for sqlplus, an Oracle SQL client, for UNIX and UNIX-like platforms. The difference between GQLPlus and sqlplus is command-line editing and history, plus table-name and column-name completion.

%prep

%setup -q

%build

aclocal && autoconf

automake --add-missing

%configure

make %{?_smp_mflags}

%install

%makeinstall

%files

%defattr(-,root,root)

%doc ChangeLog README LICENSE

%{_bindir}/gqlplus

%changelog

The Source0 section specifies a source that you can refer later using

the %SOURCE0 or %{S:0} macros. You can have more than one source

(Source1, etc).

The prep section uses the %setup macro to unpack the sources. You could as well operate directly on the source files if you need to do something unconventional.

As we need make install to install the files inside %{buildroot}, we

should call make install DESTDIR=%{buildroot}, but %makeinstall is

just a macro for that.

The files section list the files rpmbuild should expect to find inside

%{buildroot} that will be the content of the package.

Note also that we don’t need to add a runtime Requires to the readline

and ncurses libraries. Because the executable is linked against the ones

installed by the -devel packages, it will be scanned and the right

Requires injected:

$ rpm -qp --requires gqlplus-1.15-0.x86_64.rpm libc.so.6()(64bit) ... libncurses.so.6()(64bit) libreadline.so.7()(64bit) oracle-instantclient-sqlplus ...

These symbols are provided by the right package, so the solver will match them:

rpm -q --whatprovides 'libncurses.so.6()(64bit)' libncurses6-6.0-19.1.x86_64

For more information on how to build packages for various types of software, visit the openSUSE Packaging Guidelines.

Building in a real build environment

Building this way means the build environment is our system. If a

package is in BuildRequires, you will have to install it in your

system first.

If the software you are building links against some library only if it

is available, even if you don’t mention it in your BuildRequires, if

that library is present in your system, it will taint the build and make

configure find it.

What if you want to build against only the packages that are in the build requirements?

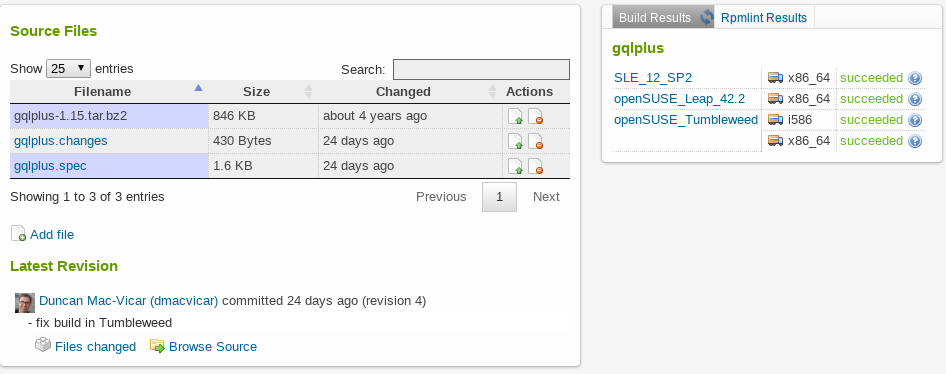

The Open Build Service

The Open Build Service allows to build packages for multiple distributions and architectures. Visit the Help Material section of the website for a deeper introduction. For the package we are building, you can get an account at the openSUSE Build Service instance. Go to your “Home Project”, “Create New Package” and upload the spec and sources. See the new package workflow for more information.

You need then to configure some target distributions for your home project. That can be one base distribution or another project. This shows the power by allowing building based on layers that can override things from previous layers.

Add the most popular SUSE distributions (latest Leap and Tumbleweed) and your package will be built automatically. A repository will be published automatically and made available for public consumption.

Every time the sources changes, the package will be rebuilt, and if you have more packages in the same project, they will be rebuilt in the right order and re-published.

Open Build Service can not only build packages, but also images from those packages. All SUSE products and the openSUSE distributions are built using the Open Build Service. Contributors basically submit new sources, and the Open Build Service takes care of assembling it all (openQA takes later care that it works).

Using the Build Service locally

With the osc tool you can checkout packages from OBS, make changes and

resubmit them.

$ osc co home:dmacvicar gqlplus A home:dmacvicar A home:dmacvicar/gqlplus A home:dmacvicar/gqlplus/gqlplus-1.15.tar.bz2 A home:dmacvicar/gqlplus/gqlplus.changes A home:dmacvicar/gqlplus/gqlplus.spec At revision 4.

The most interesting feature is the ability to build locally. “We

already did that!” you may think (rpmbuild). However, osc allows you

to build in an isolated environment (either a

chroot jail or a virtual

machine), setting up that environment automatically using the

BuildRequires of the spec file, and also allowing you to build against

a different distribution than the one you are running.

$ cd home:dmacvicar/gqlplus $ osc build openSUSE_Leap_42.2 ...

Improving the package

When you build a package in the build service, you will find out that in addition to the automated magic that injects dependencies, there is a bunch of checks being done to the package.

Yes, those checks are quite pedantic. It is the only way to ensure quality and consistency when a product is assembled from thousands of sources by hundreds of contributors.

The spec-cleaner tool can help you keeping your spec file in shape:

$ spec-cleaner -i gqlplus.spec

For example, it can help you converting BuildRequires: foo-devel

dependencies to BuildRequires: pkgconfig(foo). If a -devel package

installs a pkg-config module, a Provides: pkgconfig(foo) is

automatically injected. If the build process (./configure or

Makefile) uses pkg-config to find the software, it makes more sense

and it is closer to reality to depend on pkgconfig(foo) being present,

regardless of which -devel package provides it.

For post-build checks, you can get more information about how to fix them in the openSUSE Packaging Checks page.

Changelogs

Until now we have left the %changelog section empty. Some

distributions write there the history for the package. SUSE-flavored

distributions keep the

changelog

in a separate .changes file. To quickly generate or update it, you can

use osc vc in the directory containing the spec file and the sources.

The editor used by osc vc is determined by the EDITOR environment

variable just like for most git commands.

Finding the devel package on OBS

When contributing to an already-existing package on OBS, it is usually

best to submit any change requests to the project where that package is

developed. It is easy to find the devel project using the develproject

(dp) command:

$ osc dp openSUSE:Factory rsync network

Create a branch and a local checkout of the package using the branch

command:

$ osc bco network rsync A home:dmacvicar:branches:network A home:dmacvicar:branches:network/rsync ... At revision 11d4f594469a6679d30ae05f8b2187fd. Note: You can use "osc delete" or "osc submitpac" when done.

Now, you can make local changes to the package, for example adding a

patch to be applied to the sources after unpacking the source tarball.

You can then build the package locally as described earlier using

osc build.

Once you are happy with the package, you can commit it to your personal

project on OBS using osc commit. The build service will then build the

package remotely, so this step may reveal more issues (for example if

building on the ARM platform as well) that need to be fixed before

submitting the change to the devel project.

Once everything builds successfully on the build service as well as

locally, you can create a submit request to get the new version merged

into the devel project. To do this, use the submitrequest (sr)

command:

$ osc sr

When the package is a branch from an existing project created using the

branch command, the build service remembers where the package was

branched from and automatically creates the submit request to that

location. If you want to override this, simply pass the project name as

an argument to sr: osc sr openSUSE:Factory. This should rarely be

needed, however.